Transubstantiation

No matter our faith, we all need to believe in transubstantiation. I’m not talking about bread and wine or some figure on a cross; I’m talking about that peculiar magic of turning the meaningless, routine tasks of your day-to-day life into something meaningful, into something holy. Turn everything you do into a sacred ritual: your morning routine, that cup of coffee, your drive to work, answering all those emails, vacuuming, cracking open a beer, ordering DoorDash, brushing your teeth, taking your pills.

Our lives depend on a peculiar kind of magic. We possess the unique and awesome ability to take things that mean nothing in-and-of-themselves and turn them into the most meaningful of things. Show me a flag, and I will speak of a great nation. Take me to the river, and I will emerge reborn. Point to the night sky, and I will trace tales of gods and fortunes still to come. We transform everything in the world around us — a world that has no a priori meaning — and turn it into symbolic patterns and narratives that give our lives meaning and purpose. We turn these symbols and stories into dramatic rituals, and by doing so make manifest that meaning. Out of thin air, we turn nothing into something. Voilà!

Symbolic ritual is fundamental to any spiritual practice. Baptism initiates you into the faith, into the herd. Confession and fasting cleanse and renew. Recitation and prayer are conduits to the divine. When you participate in ritual, you transform the profane space of meaninglessness into the sacred space of meaning. In the Catholic Church, the Eucharist is, perhaps, the most sacred of rituals. The consumption of bread and wine memorializes Christ’s sacrifice and symbolizes spiritual nourishment. Fundamentalists believe in transubstantiation — that the bread and wine literally become the body and blood of Christ. The mystical becomes material. For the faithful, the ritual of the Eucharist is an affirmation, the fulfillment of a redemptive promise.

But what happens when you don’t believe? When you’ve cast off the mysticism of the 6th century? When you journey in a world of matter absolute, a world devoid of symbolic import? When bread is bread and wine is wine? What happens when the magic is gone? What then?

God may not be dead, but he’s certainly bleeding out.

The number of Americans who regularly attend religious services has been on the decline for decades while the number of Americans who identify as atheist or agnostic has risen sharply. According to recent Gallup polling, “Two decades ago, an average of 42% of U.S. adults attended religious services every week or nearly every week. A decade ago, the figure fell to 38%, and it is currently at 30%.” That’s a 12% decline over the last twenty years. At the same time, the percentage of Americans who have no religious affiliation has more than doubled, from “9% in 2000-2003 versus 21% in 2021-2023.”

In real numbers, that’s nearly 42 million Americans who’d rather sleep in on the weekend. More and more people don’t need god. They don’t need him to explain the mysteries of the universe, to offer moral guidance, to offer a community of likeminded people, to offer comfort in times of despair. Perhaps the proliferation of chaos, violence, suffering, and inequity at a global scale is enough for many to reject the paradoxical narratives of a loving, omnipotent god. Perhaps the promise of an afterlife just seems far-fetched. Perhaps Pascal's wager is a losing bet.

Like many millennials, I cut bait on the whole Jesus cult decades ago. The more I read, the more secular wisdom and art I was exposed to, the less I was convinced of that particular brand of magical thinking, of the feeble certainty that grounds fundamentalism.

Still, an atheist needs something to believe in. We still need to turn a meaningless world into a meaningful one. We still need some secular rendition of transubstantiation. So, I’ve replaced hidebound religious symbols and practices with more inclusive, humanistic symbols and rituals. I’ve found new, more intellectually and spiritually fulfilling paths of enlightenment and transcendence.

I’ve traded homilies for rock ‘n roll.

Music is a straight shot — an emotionally and psychologically powerful medium awash in signs and signifiers. Three chords and the truth, that’s enough for me. Thus, I am always seeking artists who offer some new way of being, who write songs that wrestle with the existential struggles of everyday life.

One such artist is MJ Lenderman. Lenderman is this generation’s slacker rock idol; he’s a savvy and clever lyricist who deftly narrates the current milieu. Lenderman does for songwriting what Raymond Carver did for the short story — pruning overgrown images into introspective, surreal, moving lyrical topiaries. Amidst soundscapes that gambol between avant-garde folk, anti-countrypolitan, blasé Americana, hooky grunge, and nerdy shoegaze, Lenderman sermonizes.

Lenderman’s songs are replete with Biblical allusion. Six of the nine songs on his most recent album, Manning Fireworks, allude to the Bible and religion. On the title track, a character opens “the Bible in a public place” and turns to “the very first page” before launching into a “tired” lecture on “original sin.” On the next song, “Joker Lips,” Lenderman sings that “Every Catholic knows he could’ve been the pope.” The leading role in “Rudolph” is played by a horny seminarian who “flirts with the clergy nurse ‘til it burns.” “Amazing Grace” gets a shoutout on “Wristwatch,” and Noah’s ark takes the spotlight on two songs near the end of the record. Supplication is the subject of the penultimate tune “On My Knees.” Lenderman proclaims "everyday is a miracle” while he stares out the window “speaking in tongues.”

The album is likewise populated with restive, wayward, post-pubescent young men clumsily fumbling their way through life without a clear purpose. They are mostly bored and lonely, lost and yearning, sad and vulnerable. These are feelings they fight against; they fight boredom, hangovers, each other, themselves. These are young men, as Lenderman sings on “Rip Torn,” who “need to learn / How to behave in groups.”

While others manage to find “passion” and “purpose” during their terminal paths around the sun, the young men in Lenderman’s songs spend a lot of time in their rooms: listening to Clapton, watching Men in Black, playing Guitar Hero. When they do get out, they seem hellbent on transforming the banality of their lives into something exciting (if not absurd and self-destructive); they sneak backstage, play the horses, shoot fireworks, take shots of Kahlúa, get DUIs while riding scooters, rent Ferraris, roll the dice in Vegas. They can act like real jerks. Jerks caught in the Neverland between post-adolescence and adulthood. Jerks no one gives a shit about. Jerks who don’t give a shit about you. Jerks — like some Jackass Generation 2.0 — doing all manner of stupid stunts to distract them from the existential question haunting every moment.

No amount of inane fun or peril can obfuscate the truth, however. These young men know that they will live and die and be forgotten. It’s almost as if every dangerous, terrorizing stunt they engage in is some desperate attempt to make them feel seen and heard, to offer them a chance to impress themselves on those who ignore them. These are young men in crisis. And they know it! In the final song on the record, “Bark at the Moon,” the unadorned lyric “SOS” sits hauntingly between the second and third verse.

Sure, they beat off in the shower, binge drink, and take dopey risks, but this generation is not irredeemable. Quite the opposite. These young men desperately seek meaning, acceptance, affirmation, love, and human connection.

It’s no accident that the lost souls in Lenderman’s songs are juxtaposed in harmony with all these Biblical allusions. In a world where god is dead (or on life support), in a world devoid of religious ritual, the everyday absurdity of their lives needs to be transfigured into something meaningful. In this way, Lenderman’s songs often feel more like agnostic hymns than rock tunes. They feel like the soundtrack to a new communion.

No matter our faith, we all need to believe in transubstantiation. I’m not talking about bread and wine or some figure on a cross; I’m talking about that peculiar magic of turning the meaningless, routine tasks of your day-to-day life into something meaningful, into something holy.

Turn everything you do into a sacred ritual: your morning routine, that cup of coffee, your drive to work, answering all those emails, vacuuming, cracking open a beer, ordering DoorDash, brushing your teeth, taking your pills.

Lenderman’s right: everyday is a miracle. All you have to do is believe it. Voilà!

Content Creation or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Algorithm

Art is NOT content. And nobody started writing songs because they wanted to “please the algorithm.” We started playing music and writing songs to please ourselves, to connect with others, to express the often ineffable experience of being human. We want to make art, not generate content.

Fuck TikTok. Wait. Let me clarify. FUUUUUUUUUUUCK TikTok. It is not a medium for artistry. It is, like so many other social media platforms, designed to turn art into a commodity, to turn artists into shills, to turn music into muzak.

A significant segment of TikTok’s business model is TikTok for Artists. In bold headlines, they profess that hocking your songs on TikTok will “amplify your music.” It claims to do so through increased “exposure,” building “connections” with fans, and driving “engagement” so that you can "monetize" your music. And, as TikTok claims in a recent impact report, musicians on TikTok are twice as likely to have their music discovered and shared, are more likely to get more streams on platforms like Spotify, and are bound to sell more merch.

Hell yeah! Tell me more, right! Where do I sign up? I mean, you are an unknown songwriter who wants to share your music with as many people as possible. What’s not to love?

You head to YouTube to unlock the formula to becoming the next Zach Bryan. Undoubtedly, you’ll find Jesse Cannon — bespectacled and smirking in front of some green screen graphics. Videos on his “Musformation” channel promise you “Game Changing Tips” and “Weekly Hacks” that will grow “ANY MUSICIAN from 0 to 1,000,000 Fans.” Cannon promises to teach you how to build a fan base “THE RIGHT WAY!!!” so that you will get “MILLIONS OF STREAMS While You Sleep.”

Cannon’s most popular videos are 25 minute, meme-filled screeds on the “4 Rules” that will get you to those promised 1,000,000 fans. He updates these videos yearly. This is the one from 2024. You can trust Cannon because “unlike these other YouTubers” he “does this work every day.” He works with “tons of musicians on their ascent to building a huge fan base.” And he assures you within the first 60 seconds that he is not “another one of those YouTube con-artists who is selling a course.” (Though he does offer a range of paid music marketing services).

Unlocking the TikTok algorithm is vital to Cannon’s strategy because uploading and promoting content on TikTok is free. Like he says: “as long as you have some lighting, a decent camera on your phone, and study how to do TikTok and the nuances of it,” you can “blow up for no money.” Cannon’s topline advice, then, is “Understanding the Role of Algorithms in Music Discovery.” It’s simple: appeal to algorithms. You should “deliver music in the way the algorithm likes,” and you must "follow the rules of that algorithm.” That means releasing a new song every two months and promoting the hell out of it on TikTok and other social media platforms. These campaigns to please the algorithm are long — 12 to 18 months of uploading video after video after video after video. You end up spending far more of your creative energy making slop content than writing songs.

It’s worth pausing here to define some terms.

ALGORITHM: Algorithms are basically a set of programming instructions designed to complete a task or solve a problem. Getting and keeping your attention is the sole task of social media algorithms. They are designed to “feed” you a steady “stream” of content that you like based on what you’ve watched or even paused on previously before scrolling up. An oversimplification of this is: “If TikTok User A watches a cat video, then give TikTok User A more cat videos.” It’s basically the pleasure principle on shuffle. Because social media platforms make money off your attention, the longer they can keep you doom scrolling, the more ad revenue they generate. Social media algorithms, then, are finely tuned to keep you watching. New content is the lifeblood of these zombifying beasts.

CONTENT: You’ll hear this word over and over and over again in the echo chamber of music marketing. Content is the daily barrage of videos you make to get people’s attention by connecting your song to ever-changing TikTok trends. As Cannon puts it, the game is all about saturating the algorithm with content “to keep everyone’s attention spans engaged.” He emphasizes: “you’re also competing with a lot of people for attention" so you must “continually remind people” about your song. You do this “by over and over again showing them memes and reminding them to build a relationship with the song.” As it turns out, algorithms love memes.

MEME: Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins coined the term “meme” in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene. He writes that a meme is a "unit of cultural transmission or a unit of imitation" which flourishes in human societies. Put simply, memes are infectious ideas that manifest in imitative behavior. Dawkins was particularly perplexed by why certain memetic ideas — ones that are obviously harmful to our species’s survival — persist and proliferate. Which is why Dawkins refers to memes as a sort of “mind virus.” And that’s where the notion of the internet meme takes shape. Social media platforms are the quintessential “memeplex,” a space where nonsensical content goes “viral” and spreads rapidly from person to person. (See Gen Alpha’s obsession with brain rot). Because we spend so much of our lives on social media (the average teenager spends almost 5 hours a day scrolling), internet memes are the cultural currency of the day, the means by which one connects and communicates with others online.

So, if you’re a musician who wants to go from 0 to 1,000,000 fans, you should stop worrying and learn to love the algorithm.

In the intro to Cannon’s how-to videos, he concedes right away that this memeified-content, fire-hose strategy isn’t appealing to most artists. No shit, buddy. Art is NOT content. And nobody started writing songs because they wanted to “please the algorithm.” We started playing music and writing songs to please ourselves, to connect with others, to express the often ineffable experience of being human. We want to make art, not generate content.

Art making is an ancient, elemental, and sacred human practice that has existed since the dawn of human consciousness. It’s one of our greatest and most important inventions. We make art to inject beauty into an insufferably bleak world, so that we can turn the motley nature of being into something to behold. Novelist John Cheever was right when he said that "Art is the triumph over chaos."

From a strictly evolutionary perspective, art making doesn’t make sense for the survival of the species. Painting pictures or playing the flute doesn’t put food in your belly or help you avoid being eaten by some hungry beast (though it might get you laid). But I am not trying to be dramatic when I say frankly that music and songwriting have saved my life. Emotionally, psychologically, and spiritually, our instinct to make art may be the very thing that helps us endure the trials and tribulations of being. Art does more than help us survive, it allows us to live.

Novelist Steven Pressfield put it bluntly in his book The War of Art: “To labor in the arts for any reason other than love is prostitution.” He’s right! To defile your art by transmogrifying it into soulless content is to turn the sacred into the profane. And that’s what TikTok is — a space where artists are invited to sell their soul to the algorithm for the chance, the infinitesimal chance of becoming a viral meme. Fuck that, man. FUUUUUUUUUUUCK that!

With a Little Help from My Friends

One of the best parts of being a songwriter and musician is that you’re never on an island; you’re never a “solo artist.” You're always working in tandem with so many talented and interesting people all the time. What you create is never yours alone.

Thesis: There is no such thing as a “solo artist.”

I’ll start my exposition with the act of songwriting. Most imagine the lonely writer in some sacred space welding melody to lyric in a spark of inspiration — the muse conducting every move. The truth is less romantic. Songs are written in fragments, worked on deliberately over long periods of time through rather boring routines that the artist can (mostly) rely on. The even more real truth is that a lot of songs come to being through skillful appropriation. Let’s just call it outright theft. And this is where the myth of the “solo artist” begins to crumble. At the very least, songwriting is a collaborative process in that all songs are inspired by other songs, by other songwriters.

Will I Only Harvest Some is my first release that was written in full with someone else: my good friend and talented songwriter and musician, J Seger. The very idea of the record was lifted wholesale from one of our favorite songwriters: Neil Young. Over the years, J and I have had numerous conversations about our mutual appreciation for Young’s work. It was during a trip to Asheville, NC, in 2022, when we were sitting around, fiddling on guitars, that we got to talking about Young’s Harvest. We were trying to put our finger on just what makes that record so great. We ended up writing a song, “Can You Understand,” in our attempt to capture and reinterpret the magic of Young’s 1972 magnum opus. You see, the very idea of our EP came in conference and partnership with Neil Young. Without those songs, we wouldn’t have written the songs on Will I Only Harvest Some.

And, of course, J and I wrote all the songs together. In fact, working collaboratively with someone else to write a song is more the norm than the exception. Take the most commercially successful artists you know; nearly all of their songs are co-writes. “TEXAS HOLD ‘EM” off of Beyoncé’s Grammy winning Cowboy Carter has six songwriters: Beyoncé, Brian Bates, Elizabeth Lowell Boland, Megan Bülow, Nate Ferraro, and Raphael Saadiq. Indeed, almost all of the 26 songs on that album are credited to multiple songwriters. (The only tunes with a single writer: “Jolene” by Dolly Parton and “Oh Louisiana” by Chuck Berry.) Check out the best selling albums of the 21st century. The biggest pop hits by the likes of Adele, Eminem, Nora Jones, Lady Gaga, Amy Winehouse, Taylor Swift, Justin Timberlake, and Pink were co-writes. Hell, Jack Antonoff alone has co-written seemingly every pop hit since 2013. None of these folks are sitting alone in some quiet room trying to think of a good word that rhymes with “name;” (it’s “flame,” by the way).

I still cherish the long weekend I spent with J in the spring of 2024 writing five more tunes for Will I Only Harvest Some. Working with someone else — someone whose musical talents I admire and whose compositional instincts I trust — opened me up to new and interesting ways of conceiving of what a song could be. There’s no way I would have come up with those chord changes or rhythmic patterns or lyrical images or melodic and harmonic contours by myself. These songs could only have been written by J and me together, through the marriage of diverse artistic perspectives and through the negotiation required to bring these songs to fruition. They are the better for this aesthetic partnership.

Let us now turn to the recording process. No matter who writes a song, recording is necessarily collaborative. J’s instrumental handiwork is all over Will I Only Harvest Some. That sweet harmonica and tenor guitar on “Can You Understand:” J. The delicate acoustic picking on “Paradise:” J. The piano and guitar solo on “My Intuition:” J. The groovy psychedelic effects on “Endless Summer Blue:” J. The hypnotic and dissonant fuzz guitar and bass line on “The Water’s Song:” J. Neither J nor I play the drums. That’s Emily Easterly behind the drum set, and that’s Clay White playing the horns on “Elvis at Graceland 1965.”

We recorded a lot of the acoustic guitar and vocal tracks at Deep End Studio in Baltimore, MD, which was built by owner, producer, and engineer Tony Correlli. Tony’s expertise and influence is all over the record. Those aforementioned horns on “Elvis at Graceland 1965” were composed and arranged in collaboration with him. The vocal harmonies were conceived with him, as well. So much about how the record sounds is due to his influence and ideas. Where you record something, how you record it, how you mic it — all of these important decisions depend on a competent, patient, and encouraging studio wizard like Tony.

Conor Kenahan mixed and mastered Will I Only Harvest Some. We went through seven rounds of recalls before we landed on the final mixes. So many important decisions were made collaboratively during this process. The types of effects used, track levels, how instruments and vocals are panned — these choices have to be made for each and every song. Everyone’s input matters, and every choice is vetted and negotiated by, in this case, three people who all want every aspect of the record to sound great. Conor even recut the drums on “The Water’s Song” when we weren’t hearing the dynamics we wanted. So, in every possible way, these songs sound like they do because of Conor’s finely tuned ear and talents.

You get the idea: when I listen to Will I Only Harvest Some, I don’t hear me. I hear this beautiful concert of influences and collaborators.

A little more than 400 years ago, poet John Donne penned the timeless lines: “No man is an island, / Entire of itself.” He’s right. One of the best parts of being a songwriter and musician is that you’re never on an island; you’re never a “solo artist.” You're always working in tandem with so many talented and interesting people all the time. What you create is never yours alone. And, of course, once you release your music into the world, it belongs to everyone who listens to it, to everyone but you. You’re but a small part of some mystical ritual that transcends place and time and any individual person.

It’s true: When it comes to music, you’re never alone.

Dreams to Remember

Whether awake or asleep, aware or unaware, your mind is always humming away, using innate methods older than you could imagine to help you process and thrive in a world that is likewise more complex than you could imagine. Dreams have evolved to become the main conduit between ourselves as conscious agents and the unconscious workings of our minds.

For years, it was the roller coaster dream. As the coaster climbed the steep hill toward the first big drop, I realized I wasn’t strapped in tight (or at all). Then, it was the baseball dream. I couldn't throw the ball to the plate no matter how hard I tried. I’ve had a vast array of falling dreams and numerous dreams where my legs are paralyzed as I am being chased by some menacing figure. There are the classroom dreams — a test given that I hadn’t studied for or, as the teacher in the dream, a classroom of miscreants I couldn’t manage. And then there is the occasional dream where I’m walking around only partially clothed or completely naked.

Not all my dreams are so dark (or embarrassing). Some mornings I awake elated; I dreamed I could breathe underwater and explore the vast majesty of the ocean’s depths. Or, better yet, I’ve figured out how to fly. More recently, I am lucky to have the image of my late father visit me in my dreams. He tells me he loves me, and we embrace and cry together.

I imagine some of these dream scenarios ring familiar. We all dream. But why? Our biology has been finely tuned over millennia through the messy trial and error of evolution to give us the best possible chance of survival. Surely dreams must serve some important life function.

Theories abound on the purpose of dreams. Biologists and neuroscientists have proposed that dreams help us regulate and process complex emotions, that they function as a sorting mechanism, helping us file away and remember important (and sometimes seemingly unimportant) things from our day-to-day lives. Other theories suggest dreams are like exercise for our brains, keeping us neurologically fit by breaking the cycle of repetitive daily tasks. Award winning novelist Cormac McCarthy theorized in a recent article in the science magazine Nautilus that dreams are the primary pathway for unconscious thinking to become conscious. He argues that dreams are pre-lingual and meta-lingual and that they offer us life instruction given in the form of “picture-stories” we are meant to interpret. Dreams, he suggests, are the way our unconscious helps us solve practical and psychological problems.

In his seminal work The Interpretation of Dreams, Sigmund Freud wrote that dreams offer us a chance to realize our latent and unconscious desires. Dreams are a kind of wish fulfillment. Through analyzing our dreams, Freud proposed, we might untangle repressed desires and conflicts that manifest themselves symbolically in our dreams. Freud’s protégé, Carl Jung, took these theories a step further, suggesting that dreams offer us access to not only our own subconscious but also to a collective unconscious where the inherited and universal archetypes of all sentient life dwell. This collective unconscious, he theorized, is the common wellspring of all mythology and art.

Which brings me to my main point. All acts of creation or discovery are a kind of joint mental effort. Your mind is working simultaneously at conscious and unconscious levels to help you make decisions and solve problems. Whether awake or asleep, aware or unaware, your mind is always humming away, using innate methods older than you could imagine to help you process and thrive in a world that is likewise more complex than you could imagine. Dreams have evolved to become the main conduit between ourselves as conscious agents and the unconscious workings of our minds.

Not surprisingly, dreams have been the genesis of important discoveries in math and science and the seed of artistic creation. The basis for what we call the scientific method: René Descartes dreamed it. The discovery of the chemical structure of benzene: Friedrich August Kekulé dreamed it. The movement of electrons around a nucleus: Niels Bohr dreamed it. Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem Kubla Khan: a dream (with a little help from opium, sure). Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: a dream. William Blake’s and Salvador Dali’s paintings: you guessed it, dreams. Hell, James Cameron even dreamed up the image of the Terminator!

There are great stories of musicians dreaming songs. Keith Richards wrote the guitar lick for “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” in his sleep. He recalls half waking up, hitting record on his Philips cassette player, and playing the riff he heard in his dream. Coming to the next morning, he “had no idea [he’d] written it,” he claimed in his autobiography Life. “The miracle,” he continued, “being that I looked at the cassette player that morning, and I knew I’d put a brand-new tape in the previous night, and I saw it was the end.” The rest of the tape was him snoring away. Paul McCartney claims to have written “Yesterday” and “Let It Be” in his dreams. The melody to “Yesterday” seemed so familiar and quintessential that he thought he had simply dreamed the melody from an old standard he had bouncing around in the back of his head. And “Let It Be” came from a dream he had of his late mother. McCartney said that in the dream his mother told him, "It will be alright; just let it be."

In interviews, songwriters often admit that they don’t know where a song came from, that they don’t know how they wrote it, or that they wrote a song in a trance. You hear them talk about songs as gifts or as divinely inspired. Read Paul Zollo’s Songwriters on Songwriting; nearly every artist describes part of the process as a mystery. I don’t think these folks are trying to be evasive or mystical. The universal experience is that a significant part of the creative process occurs beyond our conscious awareness. And when a musical idea makes its way from our unconscious mind to our conscious thinking, it feels like something that came from outside of ourselves. It feels like something that was sent to us.

I don’t think any of this dream-creation is an accident, however. Most creative spirits have unwittingly (and probably out of desperation) trained their minds to dream about particular problems they are trying to solve. Because it’s all they are thinking about! Harvard Medical School psychologist and author of The Committee of Sleep, Deirdre Barrett, calls this skill “dream incubation.” You can train yourself to intentionally dream about a problem, increasing your chances of coming up with a solution.

A similar method is proffered by Jeff Tweedy in his instructive and entertaining book How To Write One Song. Tweedy champions techniques that put you “consciously, in the path of your subconscious.” He adds: “We carry around a lot of stuff we don’t always know how to get to, but it’s there.” One way Tweedy has gained greater access to the magical “stuff” of the subconscious is by thinking about songs before he goes to bed and right when he wakes up. In his sleep he can “really untangle” the more challenging musical ideas he is working through during his daily writing sessions. He states plainly: “I truly think I do a lot of my best work while I’m asleep. I often wake up with the last musical puzzle I was contemplating completely resolved.” By writing as soon as he wakes up, Tweedy is able to “combine [his] semi-sleep state with the rhythms and melodies that have been danced to in [his] dreams all night long.”

In my own music making, I’ve been trying to become more attuned to the ideas swimming around in my subconscious mind. I’m trying to develop skills, habits, and routines that keep that portal between my conscious thinking and unconscious thinking open and flowing. I’m working on a new batch of songs — something I hope will become a new record — and I am writing exclusively on electric guitar. I’m obviously going for a different feel and vibe, and I’ve been listening to a lot of late 90s and early 2000s alternative rock. Which is to say I’ve been listening to a lot of Oasis. I’m in awe of how simple yet anthemic and enchanting an Oasis song can be. For months I’ve been mulling over how to write that kind of song. Obsessively. It’s almost become my mantra: What Would Oasis Do?

And then I dreamed a song. I woke up in the middle of the night with a melody in my head. It was so clear and present. I grabbed my phone from the nightstand and recorded what I heard to a Voice Memo and jotted down some seemingly random words in my Notes app. It was almost like I was taking dictation. Then I fell back asleep, still humming the tune as I drifted off.

I meditated on that melody and those lines for a few days before I sat down to work on the song, trying to bridge the motley perfection of my dream with the conscious act of actually writing a song: the chords, the structure, the words. In little time, I had written “Staying Alive,” a song I just recorded live at Deep End Studio. I don’t think I exactly got the catchy Oasis tune I’ve been wanting to write, but I do think I captured pretty well the chorus I heard in my dream. That I dreamed a song in and of itself is proof enough that I’ve got a capable co-writer in my unconscious mind.

I am a firm believer that the ritual of art-making requires open pathways between our conscious experience and unconscious mind. We need help. Often, we don’t know what we’re doing or, perhaps more importantly, why we are doing it. The good news is that we have a creative guru in our subconscious. (One that seems to prefer surrealist imagery, I’ll admit). Dreams are a portal to a very old, universal, and fundamental part of the brain, to a way of thinking evolved to help us process and understand the world and ourselves beyond language or reason. Dreams help us reckon with failure, inadequacy, uncertainty, and fear. They fulfill our desires and set us free from the restraints of day-to-day life. And, occasionally, they help us tap into the majesty of song.

Whatever you need, you’ll probably find it in your dreams.

Ornamental Monsters

We remain pilgrims stumbling through the fretful void, and the only thing we have to guide us are stories. No other creature seeks (or needs) to fill the mechanistic universe with tales of being, narratives of origins and destiny. We are the lone myth-making creature.

“For although each man among them was discrete unto himself, conjoined they made a thing that had not been before and in that communal soul were wastes hardly reckonable more than those whited regions on old maps where monsters do live and where there is nothing other of the known world save conjectural winds.”

~Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian

Debates over the source of consciousness are old and legion. I don’t intend to wade into those deliberations or even proffer anything close to a unified theory of the brain and mind; instead, I’d like to propose a simple enough hypothesis. Whatever the physiology of consciousness, its origins were most certainly accompanied by a novel intuition: Why?

The dawn of consciousness marked our species’ transition from darkness to light, from instinct to contemplation, from ignorance to awareness, from paradise to fear. This cognitive leap must have been accompanied by endless questions (even if we didn’t have the language yet to ask them): Why did the sun rise? Why is it setting? What will happen when it sets? How can we make it rise again? What is the sun, anyway? Every moment had to feel like a possible end. Consciousness begot concerns over the frightening natural world and our fragile, vulnerable place within it. To survive, we required answers to these elemental and existential questions.

We remain pilgrims stumbling through the fretful void, and the only thing we have to guide us are stories. No other creature seeks (or needs) to fill the mechanistic universe with tales of being, narratives of origins and destiny. We are the lone myth-making creature.

Please do not confuse my use of the word “myth” with its pejorative: myth = not true. Myths are essential to our being. They were to ancient peoples and are still so. Allow me to offer a rather lengthy exposition on what I mean when I say “myth.”

Myths singularly found civilizations and cultures.

Myths — whether they are based in the imagination, on historical events, or on observable facts — are metaphorical narratives constructed and organized around symbolic images and signs.

Myths create a sacred, social order in a violent and chaotic world and imbue that world with meaning, allowing us to participate in an existence full of significance and import.

Myths point to a transcendence or power beyond ourselves and place us in a realm of shared, collective meaning which surpasses all relative space and time.

Myths provide a moral compass for social groups, a guide to right and wrong according to the customs and mores of the time.

These symbolic stories allow us to weave varying aspects of understanding into a single, cohesive framework. They offer us guidance for why and how we should live. Their essence permeates all cultural expressions: literature, art, religion, history, science.

How about this analogy: Think of myths as a sort of map. In a chaotic and unpredictable world, they help locate us in a particular place and time and offer us guidance for which life path we should choose. They provide figurative routes for how to get from here to there. These narrative maps are all we have to help us navigate the incomprehensibly vast expanse of Reality.

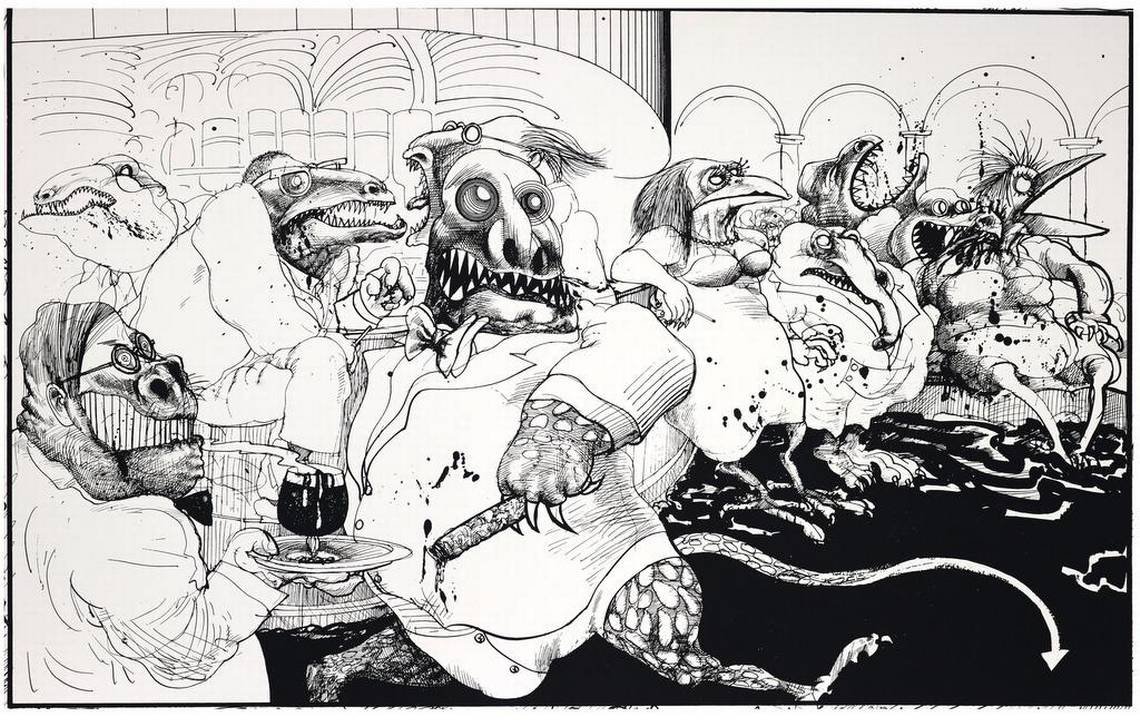

Essential to myths are monsters, of course. Picture that half-human, half-beast from your childhood fairytale. Or, picture the dark, violent specter from your favorite horror film. Monsters inhabit torturous spaces in our mind. We can agree that monsters are scary. They symbolize what we don’t understand. They symbolize our fear of the unknown. They symbolize danger, in all its manifestations and forms. They represent a threat to our sense of self, to our sense of being, to our very existence. Scary beings inhabit a scary world.

Consider early depictions of monsters. Bridging our development from the Dark Ages to the Enlightenment, early cartographers adorned their maps with mythological sea monsters. Perhaps the most famous of these is Olaus Magnus’s 16th century Carta marina.

In his book Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps, scholar Chet Van Duzer offers a common explanation for this phenomenon. Monsters on maps “serve as graphic records of literature about sea monsters, indications of possible dangers to sailors — and data points in the geography of the marvelous.” They can be interpreted, he continues, as “guardians of the furthest limits of the world.” In other words, the ocean is vast and scary, and there are things in those depths beyond our reckoning. When we don’t know what lies beyond the horizon, we imagine; we conjure monsters. It’s a plain warning: Beware to those who venture into uncharted territory!

But, Van Duzer offers a second interpretation, one that considers the artistic value of such fiends. Monsters on maps “may function as decorative elements which enliven the image of the world… emphatically indicating and drawing attention to the vitality of the oceans and the variety of creatures in the world, and to the cartographer’s artistic talent.” Van Duzer adds that Medieval and Renaissance maps containing sea monsters were “richer, more sumptuous, more extravagant.” In summary, these creatures supplant dread with an aesthetic. It might not surprise you to know that maps adorned with such fanciful beasts were sold at a higher price to the royalty and nobles who commissioned them. Thus, these mythical creatures served a dual purpose. They gave imaginative shape and color to the dangers and mysteries of the vast unknown. And, perhaps more importantly, they reflected innate artistic expression — these ornamental monsters that transfigure fear into surreal wonder.

What is art if not the ur-language of myth? Our guide to parts unknown. Through storytelling, song, and image-making we create beauty and meaning where before there was nothing absolute.

Songwriting has offered me a chance to chart a course, as Cormac McCarthy so brilliantly put it in his masterpiece Blood Meridian, to “those whited regions on old maps where monsters do live.” I am moving from darkness into light. I am venturing into parts unknown. I am deconstructing those dragons in the mist. I am decorating the void. I am trying to answer: Why?

And know, this discourse on consciousness, myths, and maps is no abstraction, no history lesson. Our day-to-day lives are filled with psychic monsters that take all shapes and sizes. Every day is a heroic quest. There is so much we do not know, so much that we fear. The only guide we have through this perilous journey are the myths we weave, together and for ourselves. And we must do more than tell ourselves these stories. We must enact them, live them, be them. We must continually examine and revise them. We must turn our very lives into works of art. If we do, then the whole journey becomes sublime — even the mythical beasts.

When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be

To exist consciously is to become aware of one’s impermanence. For some, this truth is unthinkably depressing. After all, we matter. How can it all wither away into the annals of insignificance so quickly, our existence devoured by time’s implacable black hole?

Thought Experiment: Consider, for a moment, the absolute lack of record of almost everyone’s existence prior to the invention of writing. These were people like you and me who lived rich, complex, social lives. Nothing is left of them but the faintest genetic trace.

How long will it be until you are forgotten? The moment when it’s like you never existed? If you have kids, you’ll certainly be remembered throughout their lifetime. If your kids have kids, you’ll be half remembered by your grandchildren. So that’s, what, another eighty years of memorial existence after your death (if you’re lucky). After that, you’ll be reduced to a record in someone’s file, a leaf on some family tree, a photo in a book no one opens, a series of unviewed images in some internet cloud. Given long enough, even those records will cease to be. By the end of the next century it will be almost as if you never existed. History is overflowing with the billions upon billions of people just like us: those who lived, loved, suffered, died, and were forgotten.

To exist consciously is to become aware of one’s impermanence. For some, this truth is unthinkably depressing. After all, we matter. How can it all wither away into the annals of insignificance so quickly, our existence devoured by time’s implacable black hole?

It’s worth noting that ancient and modern cultures resolve this existential dilemma with varying stories about an afterlife. Problem solved. I’m not convinced by such tales. In contrast, I think a lot about non-existence, and I find that meditating on my finite nature, on the impermanence of all things and all people, has been my very salvation. Join me, if you will, on a few (hopefully) related tangents.

Tangent 1: When my wife was pregnant with our first child, she made me aware of something called a “push present” — this being a gift you give your partner for, well, pushing out a child. (It’s kinda all explained in the name). I never know what to get my wife for holidays or birthdays or anniversaries, so imagine my dread and horror when faced with giving her a gift for bringing life into the world! My wife owns 173 pairs of shoes, 42 purses, and two jewelry boxes filled with all manner of shiny objects. (And on the off chance she reads this, I COUNTED). I just couldn’t think of another thing to get her.

Tangent 2: In one of his later works, Twilight of the Idols, Friedrich Nietzsche condenses all of his theories on reason and philosophy and religion and art into a figure he calls the “tragic artist.” The tragic artist has rejected the existence of absolute truths, has confronted the nihilistic reality of an objectively meaningless existence, and has overcome that nihilism by passionately embracing his existence and fate in spite of the absurd insignificance of everything. Ironically, it is in his fervent embrace of every moment of his pointless existence that he overcomes the sickness of insignificance and redefines the meaning of his life on his own terms. In Nietzsche’s words: “The tragic artist is no pessimist: he is precisely the one who says YES to everything questionable, even to the terrible.” He triumphs over all futility through the act of self-creation. In this sense, the tragic artist fashions subjective meaning within an ultimately meaningless existence.

On the one hand, art, as Nietzsche observes, “makes apparent much that is ugly, hard, and questionable in life.” It exposes and confronts our bleak reality. With the same brushstroke, however, the tragic artist creates art full of “courage and freedom of feeling before a powerful enemy, before a sublime calamity, before a problem that arouses dread.” Instead of nihilism, the tragic artist evokes a “triumphant state” through the act of creation, one that glorifies our existence in defiance of the existential truth: that we will live and die and be forgotten in the blink of an eye. Art has no higher purpose than to reflect the inherent tragedy of our existence while simultaneously overcoming that tragedy by conjuring beauty and meaning out of nothing!

(Back to) Tangent 1: Which brings me to “Write Me a Love Song.” (For those expecting some simple, romantic gesture here, I do apologize). I didn’t want to get my wife just any thing to celebrate the birth of our child. We chose to bring life — a life that was not here before — into existence, and that act of creation felt worthy of a more sacred gift. Diamonds aren’t forever (despite what they tell you), she has more than enough shoes, and another purse would just get tossed in with the others.

In song I tried to capture just how rich our life together is, just how necessary we are to each other in this existence that races toward non-existence. We are here, we’ve brought life into the world, and soon we will return to oblivion. Still, our life together matters — to me, to her, to our children. Each day as a family, we resurrect and renew our fragile and finite love. Our very existence together is a work of art. What else could I do but sing?

Tangent 3: In light of Nietzsche’s views — which have informed much of my intellectual stumbling for decades — I view songwriting as the primary instrument through which I can define my life as a tragic artist. It’s about far more than streams and follows. (Though, please, stream “Write Me a Love Song,” and share it with a friend!) It’s about accepting those noble truths spoken by the Buddha all those years ago: that I am impermanent, that life is suffering, and that there is no self. And still I sing. And soon my songs (and whatever beauty swims in their musical wake) will have never been.

Even so, there is no greater sense of purpose I know than creating art, and, by turns, creating myself.

The Greater Scheme

When you’ve peered behind the curtain of musical craft long enough, when you’ve lived your life with full attention to how songs are made, you don’t frequently come across lyrics that seem otherworldly. Most songs don’t bear the markings of the mystery. The lyrics of most songs seem doable, and it’s comforting to think that I could probably write something similar. But “Canola Fields” gave me the fear immediately — that this kind of writing was something I couldn’t do.

“I was thinking 'bout you, crossing Southern Alberta / Canola fields on a July day / About the same chartreuse as that sixty-nine Bug / You used to drive around San Jose.” The first time I heard the opening lines to James McMurtry’s “Canola Fields,” I was at turns dazzled and dejected. On the one hand, a living person had sat down with pen, paper, and guitar and written these poetic lines. (Nowadays, of course, it’s more likely he sat down with a computer or iPhone and a guitar). On the other hand, I couldn't wrap my head around the intimidating finesse and virtuosity of the lines.

When you’ve peered behind the curtain of musical craft long enough, when you’ve lived your life with full attention to how songs are made, you don’t frequently come across lyrics that seem otherworldly. Most songs don’t bear the markings of the mystery. The lyrics of most songs seem doable, and it’s comforting to think that I could probably write something similar. But “Canola Fields” gave me the fear immediately — that this kind of writing was something I couldn’t do. The lyrics strike the perfect balance between specificity and universality. The imagery and word choice are exact and particular; the characters are so distinct, yet the song invites you to imagine this experience as your own. It feels as close to perfection as a songwriter can get.

Take the use of proper nouns. This drive isn't just happening anywhere; it’s happening in “Southern Alberta.” These aren’t just any fields; they’re “Canola fields.” It’s not just summer; it’s “July.” And this moment reminds the speaker of a car, but it’s not just any car; it’s a “sixty-nine Bug” which is being driven around not just any city but “San Jose.” What’s so uncanny about the exactness of the location and symbolic imagery here is that it’s both unfamiliar and familiar at the same time. I’ve never been to Southern Alberta or San Jose, and I’ve never driven by Canola fields; still, I was able to immediately imagine myself on some lonesome, desolate drive at the height of summer with the windows down thinking about the past. What kind of magic trick is this — where a songwriter can weave exotic detail seamlessly with intimate experience?

And while it’s not a proper noun, “chartreuse” is a peculiar color to choose. It’s not a color — like blue or red or yellow — that can be easily placed. And once I took the time to look it up, I realized that chartreuse is a greenish/yellow color named after a French botanical liqueur produced by Carthusian Monks during the 18th century. (It tastes awful, by the way, in all its varieties). So take a look at the lyrics again, and this time move beyond the majesty of the visual impressionism. Wafting from the opening lyrics are also distinct smells. In bloom, Canola smells like cabbage. Chartreuse smells like rosemary, sage, and pine. If you immerse yourself even deeper in the lyrical dream, you can also smell the Polypropylene and plastic of the car’s dashboard baking in the July sun. The evocation of these earthy and industrial smells is not unimportant, in the song or to the listener. Smell is deeply ingrained in our emotional memory. Both smells and songs conjure memory, and that is exactly what’s happening in this opening verse. The Canola fields remind the speaker of the car his former lover used to drive while at the same time the song itself is asking the listener to remember, to connect this song with his or her own lived experience.

During each and every listen, I find the opening four lines of “Canola Fields” (not to mention the rest of the song) to be sensorially, emotionally, and intellectually all-consuming. The song takes me on a journey filled with memory, regret, and (by the end) a real shot at redemption. It’s the work of a songwriter at the height of his craft. There’s much grace to be found in art, and the more time I spend with “Canola Fields,” the more approachable, the less mysterious it seems to me. On occasion, I think I even catch a glimpse of McMurtry: the lonely songwriter, the mason toiling away at the stone.

I told my good friend and fellow songwriter J Seger that I felt like I really turned a corner in my own songwriting when I wrote “Hermès Scarf.” I’ve been stretching myself to locate that lyrical balance that McMurtry found between specificity and universality. I wanted to move beyond all those clichéd and reliable turns of phrase that seem to be the first to surface when you’re working on a song. They’re always available and could work, but these easy lines are often not worthy of the kind of song I’m striving to write. The key, I’m finding, is in word choice, in the timely invocation of proper nouns and the intentional arrangement of vivid and unique adjectives. It’s about the synchronized dance between wording, meter, phrasing, and phonology. This approach seems more attainable to me now, and I think I’m stumbling in the right direction with “Hermès Scarf.”

The first thing people do when they focus their attention on the lyrics of a song is try to imagine themselves in the song. As authors Susan Rogers and Ogi Ogas point out in their insightful book on the intersection of music and neuroscience This Is What It Sounds Like, “Talented songwriters recognize that listeners' imaginations work alongside their literal perception when they are enjoying a record. Even as we process the words, our minds are spinning out imagery and memories and emotions.” Therefore, exacting imagery has to be used in order to evoke the most vivid imaginary world. At the same time, the scenic landscape and emotional narrative have to be vague enough so that the listener can put himself or herself into the song’s situation, so that the listener can fill in the blanks left by the songwriter with his or her own life experience.

In the third verse of “Canola Fields,” McMurtry sings: “We all drifted away with the days getting shorter / Seeking our place in the greater scheme / Kids and careers and a vague sense of order / Busting apart at the seams.” How could this line not be about me?

There’s a reason your favorite songs are sacred. At times they speak for you; they perfectly express your experience and emotions. Other times, they offer you a chance to imagine a different life. Even more, they expand your understanding of other people. Expressed more concisely in This Is What It Sounds Like, “Lyrics can make us feel seen, heard, and understood.” And they do all this even though the words aren’t yours, even though the story isn’t exactly yours. Still, you step through some magical portal and become part of this deeply personal mise en scène. Within this whirlwind of language, sensory detail, and imagination you find meaning and understanding.

More and more, I am convinced that, amidst the messiness of life, songs help us in our quest to find “our place in the greater scheme.”

Just My Imagination

But, what I tell myself I am really doing is trying to find my persona: some Grecian mask I can put on to liberate myself from myself. To become something wholly different and other on stage — a vessel of sorts where the latent desires of performer and audience dissolve together in some phantasmic wish fulfillment.

Seafoam green slim jeans. Black skull t-shirt. Skull ring. Turquoise ring. Onyx bracelet. Handcuff bracelet. Chain wallet. Rattlesnake charm necklace. Sunglasses. Chukka boots (though I really want snakeskin cowboy boots).

My wife is embarrassed by how I dress for gigs. My look has all the markings of someone in his (early) forties trying to reclaim his youth. And I won’t deny that some of that developmental psychology has to be at play. But, what I tell myself I am really doing is trying to find my persona: some Grecian mask I can put on to liberate myself from myself. To become something wholly different and other on stage — a vessel of sorts where the latent desires of performer and audience dissolve together in some phantasmic wish fulfillment. There’s something beautiful and true that happens in this collective myth-making. That’s what I’m doing.

Or maybe it is just some midlife crisis.

I would argue that every artist dawns a persona on stage. It’s essential to the performance, to the collective suspension of disbelief. Let’s start with pseudonyms. Some of my favorite artists are: Robert Zimmerman, Roberta Anderson, Stevland Judkins, David Hayward-Jones, Reginald Kenneth Dwight, James Osterburg, Jr., Jeffrey Ross Hyman, Shawn Carter, Edward Severson, Calvin Broadus, Jr., Alicia Cook, Josh Tillman, Elizabeth Grant, Christopher Breaux, and Kendrick Duckworth. Never heard of ‘em, right? We all know them as: Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Stevie Wonder, David Bowie, Elton John, Iggy Pop, Joey Ramone, Jay-Z, Eddie Vedder, Snoop Dogg, Alicia Keys, Father John Misty, Lana Del Ray, Frank Ocean, and Kendrick Lamar. All these spellbinding, creative spirits — masked and notorious.

Giving yourself a new name is a rebirth. It’s a chance to grow and evolve into something you are not. You become a fictional character. You can say and do things as this figment that you would never do as yourself. A portal is opened to a place of expanded freedom and expression. In this theatrical space, everything is magnified — reality is distended. In cloak and veil we can better examine all those gaudy axioms of our rather usual but complex existence. The truth is hiding in plain sight when we all just make believe.

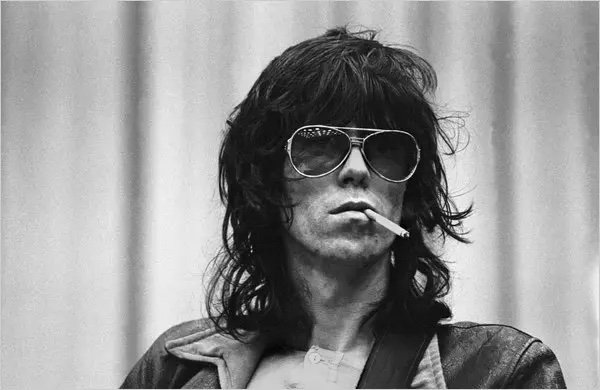

Fashioning a persona doesn't always require a new name, however. Take Keith Richards as the ideal example. He is the embodiment of THE MYTH: sex, drugs, and rock n’ roll. This guy has been on every “Celebrities Most Likely to Die” list since the 70s. He’s been perpetually on the nod for the past six decades, right? We’ve all seen the photos. I won’t deny that Richards spent most of the 60s and 70s in a narcotic haze (still somehow alert enough, I’ll add, to write most of Beggars Banquet, Let It Bleed, and Exile on Mainstreet). What’s also true, however, is that the guy is worth north of $500 million and that he kicked heroin in ‘78 and hasn’t snorted a line for more than 15 years. (Warning: bumping lines in your sixties is not recommended for most senior citizens). He’s a father, a grandfather, and has a businessman's understanding of international tax codes (which comes with the territory of being rich, I guess). So why do we imagine that the 79 year old man on stage is something more than what he really is? From our vantage, why does he appear to be a rock god?

Keith Richards’s persona has persisted because it’s necessary. First, it’s necessary for him. As Tom Waits put it in the Netflix documentary on Richards’s career, Under the Influence: “You have to have some type of armor so that you can continue to also develop as a human being, you know.… Inside that [persona] you’re still able to grow and change…. It’s kind of a ventriloquist act a lot of the time, you know, but it’s much safer than putting your own ass out there.” Personas allow artists to divorce their artistic selves from their practical selves. Personas also provide songwriters courage to charge through the emotional phalanx, through the immense fear that comes with putting your art out in the world to be consumed and judged.

Second, Keith Richards’s persona is necessary for us. Carl Jung, the philosopher and psychologist whose exposition on the persona is seminal to our intellectual history, observed the following: “The persona is a complicated system of relations between individual consciousness and society.” As we’ve seen, the persona allows the artist to conceal her true nature, but it also allows us (the audience) to conceal our true natures. It permits us to believe that such unbelievable people really do exist. If Keith Richards can will himself into something transcendent, some spirit that expresses the totality of our emotional selves in a few strums of the guitar, then so can we. All our dreams and desires are projected onto that masked man stumbling on the stage.

But such masks also trap you in some version of you that’s you but not you at all. In his epic autobiography Life, Richards admits: “I can’t untie the threads of how much I played up to the part that was written for me. I mean the skull ring and the broken tooth and the kohl…. I think in a way your persona, your image, as it used to be known, is like a ball and chain. People think I’m still a goddamn junkie. It’s thirty years since I gave up the dope! Image is like a long shadow. Even when the sun goes down, you can see it. I think some of it is that there is so much pressure to be that person that you become it, maybe, to a certain point that you can bear. It’s impossible not to end up being a parody of what you thought you were.”

All myths are really cautionary tales, in the end.

So why the colorful jeans, the accouterments of death, the chain wallet? Because really what we all want sometimes is to be someone we are not. I want to be a rockstar. I want to be Keith Richards (even though I know Keith Richards isn’t really Keith Richards). Even Keith Richards doesn't want to be Keith Richards. “I just want to be Muddy Waters,” he confesses in Life, “Even though I’ll never be that good.”

In the end, we all need personas because they help us manifest and channel our hopes, dreams, and desires. So, I’ll keep trying on different masks — looking for the one that fits best.

If you come across any deals on snakeskin boots in the meantime, send them my way.

Slouching Towards Tin Pan Alley

We know more and more about so much more, and yet we find the more we know the less we know about all there is to know. You see, art offers a complementary and contemplative narrative in juxtaposition to reason alone.

I’ve begun teaching a songwriting course to high school seniors. What I’ve discovered building and refining the curriculum is that so much of the “teaching” of songwriting is wrapped up in what I am trying to “unteach” myself as a songwriter.

First, expertise in academia is all about semantics. It’s not so much about what you know or your intuitions; it’s all about wielding the language of expertise — words and definitions that musicians have developed over the years only so that they can communicate with other musicians and other songwriters in a common tongue. This language in-and-of-itself, however, is not essential to the songwriting process. Music, afterall, preceded language.

Still, in teaching my students about songwriting, I’ve found myself hammering home vocabulary more than talking about the orphic process of songwriting. I’ve had to define musical concepts like melody and meter and syncopation. I’ve had to explain and clarify the elements of song structures: verse, chorus, bridge, pre-chorus (whatever a pre-chorus is). Sadly, I’ve been reducing the feel, the instinct, the mystery of songwriting to formulas. All the while I know that great drummers don’t need a textbook to tell them what “swing” is and that great lyricists don’t need a dictionary to define the musicality of alliteration. They just do it because it feels and sounds right.

I’ve been plagued by a sort of double consciousness as I stand before my students. Ultimately, I don’t even think you can teach songwriting. I agree with Mary Gauthier who wrote in her brilliant memoir Saved by a Song: “I don’t know of a single songwriting rule that can be universally applied. There are no absolutes in songwriting, and no one holds a monopoly on how it should be done.” She’s even more right when she admits, “I learned how to write songs by writing them.” I’d humbly add that I learned how to write songs by listening over and over and over again to the best songwriters in every era and every genre. I study music as if my life depends on it. Great art is mimicry fused with particularity. Only you can write the songs you write, but it’s best to be in musical dialogue with those who came before you.

Allow me to wander a bit: I picked up Dostoevsky’s instructive novella Notes from Underground the other day. It’s a book I taught for a few years and a book I fell in love with as a cynical undergraduate. I won’t drone on about the storyline (you should read the book), but, in summary, it’s about someone who refuses to accept the many, many formulas we’ve devised to help ground ourselves in reality, constructs we’ve invented to save us from the chaos and randomness and meaninglessness that underpins our existence. The underground man has read all the science that attempts to put everything in order, that attempts to categorize and name all things. He’s read all the philosophy about reason and beauty and truth. And what he discovers is that the truth of 2x2=4 has not unburdened him from the “sickness” — no formula will ever resolve his existential crisis of being.

Now, I’m not arguing that math and science aren’t true. I believe in the scientific method and that mathematical proofs are our only way of discovering objective facts. What I am saying is that facts alone are often not enough in response to the paradox of being. (Has the groundbreaking discovery of genetic sequencing ever helped you get through a bad day at work?) We know more and more about so much more, and yet we find the more we know the less we know about all there is to know. You see, art offers a complementary and contemplative narrative in juxtaposition to reason alone.

And this is where great songs are born, in the space where established knowledge implodes under the weight of its own limits, where great artists shatter pre-existing molds through creative inquiry. Art, if it serves any function at all, offers emotional and intellectual guidance in an existence devoid of absolute answers — in an existence where, most likely, there are no answers but only more questions.

So how should I teach my students to write songs? I’ve decided to teach them the rules and language of songwriting and insist that they break those rules and invent a new language. I am going to invite them to listen to the greatest songwriters I’ve communed with these many years and encourage them to discover the inspired and diverse ways songs can be assembled.

The craft of songwriting is about so much more than strophic or ternary song forms. It’s about more than rhyme or pitch or downbeats. I’ll admit: I can’t teach my students how to write a song, but I can certainly advise them on how not to write a song. Or, just maybe, I can offer them a calling that will help them reflect on the mystery of being.

High Fidelity

Principally, sound is the process of setting air to motion. The physics of sound is waves and pressure and velocity; it’s reflection and refraction and attenuation. But sound is also a sensation: a way of perceiving a motion we cannot see. Sound is an experience — a beautiful marriage of the physical and mental — that can be appreciated purely in only the space and at the time where and when it is being created.

“Guglielmo Marconi, the inventor of the radio, believed that sound waves never completely die away, that they persist, fainter and fainter, masked by the day-to-day noise of the world. Marconi thought that if he could only invent a microphone powerful enough, he would be able to listen to the sound of ancient times. The Sermon on the Mount, the footfalls of Roman soldiers marching down the Appian Way.”

~ Hari Kunzru’s White Tears

Space and sound: the 700 square foot storefront at Sun Studios, the Ryman Auditorium, the low-ceilinged basement at Motown's Hitsville USA, the Royal Albert Hall, the movie theater where Willie Nelson recorded Teatro, the Echo Chambers at Capital Tower, Abbey Road, the humid cellar of Villa Nelcotte in the south of France where The Stones recorded Exile on Mainstreet, Carnegie Hall, the concrete eyesore that is Muscle Shoals Sound Studio, RCA Studio B, WMGM’s Fine Sound Studios where Miles Davis birthed cool, Sound City Studios, the old church that was turned into Columbia Records 30th Street Studios, Stax Records, Trident Studios in London where Ziggy Stardust landed, 210 South Michigan Avenue, the Sydney Opera House, the stairwell at Headley Grange where John Bonham record the drums for “When the Levee Breaks,” Electric Lady Studios. You get the point. I’m obsessed with sounds produced in specific spaces at specific times.

When you play a song live, there’s no intermediary between you and the sound being produced. I am spellbound by acoustic sounds. Vibrations that emanate from instrument or mouth, produce waves that jangle air particles, pierce our ears, and are perceived, without filter, by our brains. Principally, sound is the process of setting air to motion. The physics of sound is waves and pressure and velocity; it’s reflection and refraction and attenuation. But sound is also a sensation: a way of perceiving a motion we cannot see. Sound is an experience — a beautiful marriage of the physical and mental — that can be appreciated purely in only the space and at the time where and when it is being created.

Sure, you can record sound. You can amplify it. You can digitize it and translate it into binary. But, all recordings, analog or digital, never fully capture the space in which it was made. The recording and transmission of sound is ultimately a fool’s errand. A shadow on the wall of Plato’s cave. An approximation. Further, compressed digital files like mp3s are altogether an alien language; they’re sonic pulp, a computerized bastardization of human-made sound. Digital sound is not, by design, human sound. Direct-to-disc (what was once the green dragon of high fidelity vinyl recording) is as close as you can get to capturing live sound. The wave movement of space is captured directly onto the grooves of the record. (Grooves are not 0s and 1s). But still. You put that ultra high fidelity record on, and you’re in a different space. You’re in your living room (a spot where you’ve planted, like a flag in the ground, your obnoxiously big turntable, amp, and speaker setup despite your wife’s protestation). It’s still not the same as being there when that note was played or lyric was sung.

There are some songs I play over and over again in my little basement music room. When I’m flipping through my Big Binder of Songs, I always seem to stop at Ryan Adams’s “Hard Way to Fall.” I keep playing it, first, because it’s a brilliant song, and, second, because I am trying to fully capture the essence and performance of the song this time. I am trying to achieve a certain sound — in this space at this time. Sometimes I get pretty close. Most of the time I just “cover” it and move on. I guess what I am trying to confess here is that I am aware of and in awe of the potential in that magical space I’ve procured for myself in the underground part of my house. There’s a way, I know it, to move that air with that song in such a particular way that transfiguration is possible. That space, as somewhere to reach for the sonic and emotional absoluteness of a song, is holy to me.

You know that central image on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel? Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam? That narrow but infinite space between the finger of god and the finger of man? That’s what I am going on about here, folks. There is something about live, acoustic performance that is holy and something about recorded performance and digitized music that is forever and ever a simulation. It’s the outline of the thing and not the thing itself. As someone who takes the recording of song very seriously, this truth is devastating.

So what do we do in the face of this reality, that music in its purest form — as a live performance — cannot be accurately recorded or preserved? Most people say, “Close enough. Stop all this ranting, Baker. This isn’t good for your health.” To those I offer: “You’re right. And don’t worry; I’m fine.” Practically, however, what I am trying to do now is reframe my approach to recording.

I am heading back into the studio, and this time I am going to try to prioritize the space. I am going to try to capture as close as possible the way instruments and voices sound in space. I am mulling over hard engineering questions. (A thing I am in no way qualified to do which is why producers and engineers are so important in the process). How can I make this highly orchestrated, technical, and digitized process more visceral, more live, more reflective of the space and time in which the air was shaped to wave? Acoustic performance is one way, and by acoustic performance I don’t mean just acoustic guitar. I mean capturing the actual sound waves produced by a real piano, a real amplifier, a real voice. The ideal: no direct to console recording. No synthesized sounds. No MIDIs or plugins. No recording that’s not done in real space in real time.

Of course! I am going to break this promise as soon as I get into a studio chock full of amazing technological innovations. But the aim remains fixed. Or, at least this intention will become the touchstone for the conceptual sound of the record.

This is getting technical and silly and all too theoretical. For those still reading, bless you. But, I hope what is coming across here is the pursuit of an ideal. For what is art if not the attempt to depict and capture ideal Forms? There is no higher Beauty or Spirit than the art of Song. This futile quest to preserve Song in its purest is no less absurd than other quests. It, at the very least, offers me a direction to journey.

And I Know It

I spent much of my artistic energy as a young songwriter trying desperately not to rhyme. I wasn’t trying to write “Love Me Do.” Most of the songs I write now, though, revel in rhyme. More and more I’ve grown to understand and appreciate the utility of rhyme in songwriting and the radically paradoxical freedom it endows in its constraint.

I love The Beatles. I do. But, I don’t spend much time listening to songs written before Rubber Soul. And for good reason, I’ll argue.

Last month, I was lucky enough to see Paul McCartney in concert. The show was a dream come true, and Sir Paul played with all the energy and enthusiasm of a man half his age. But, during his nearly three hour set, one song caught my attention (and triggered my cynicism, too).

“Love Me Do” was The Beatles’s debut single. Released in England in 1962, it reached #17 on the UK Singles Chart. When it was released in the States in April of 1964, it hit #1 on the Billboard Hot 100. Teenyboppers and Beatlemaniacs swooned to “Love Me Do.” What’s not to like about it? It’s catchy, up-tempo, and fun. It even has a great harmonica solo! It’s easy to sing along to, largely, I think, because of the simplicity of the lyrics and rhyme scheme. I realized though — even as I sang along with thousands and thousands of other concertgoers — that the song is completely illogical; it’s little more than a teenage nursery rhyme. I understand formulaically why “Love Me Do” was a hit for The Beatles, but artistically I think it’s one of their worst songs. It’s certainly not something songwriters should try to emulate or recreate.

I mean, what does it even mean to “love me do?” Surely, it’s meant as a command: as in do love me. But, such word reversal is most at home in the midst of some Shakespearean sonnet. Shakespeare gets a pass because of the complexity of his poetry and the masterful way he uses linguistic inversion as a highly stylized and intentional metrical device. “Love Me Do” isn’t deserving of such Shakespearean-license. “Love me do” is a nonsensical phrase, and it strikes me the more I think about it as spontaneous yet lazy writing; it’s just a silly rhyming trick.

Allow me to speculate further: Paul and John wanted to write a love song, right. So, they started with “I love you” as the foundational end-line phrase. They must have worked backward from there. There is no way Paul or John bothered with a rhyming dictionary as they impulsively scribbled down this saccharine (if not woefully immature) masterpiece. “You” is one of the easiest words to rhyme in the English language. Hundreds of words rhyme with you: blue, knew, flew, tattoo, undo, breakthrough, avenue. The list goes on and on. But, I don’t think Paul and John struggled very hard to find a more sensical rhyme. (Anyone who has seen all eight hours of the Get Back documentary can attest to the dynamic duo’s Dada approach to songwriting, even later in their careers). Somewhere in the hasty process of writing down lines that rhymed with “I love you,” “love me do” came out. Voila! A framing hook.

Hold on. I’m almost done… I’ll just add that rhyming “you” with “love me do” feels like a swing and a miss, or, dare I say, a miscue!

I smiled quizzically later that night, humming along to “Love Me Do” back at my hotel after the show. Were John and Paul being cheeky or naive? Or, more likely, were they just trying to write a hit and weren’t worried too much about the grammatical illogic of a phrase like “love me do?” They probably thought the line was funny! It certainly makes me laugh.

I spent much of my artistic energy as a young songwriter trying desperately not to rhyme. I wasn’t trying to write “Love Me Do.” An admirer of modern, postmodern, and avant-garde poetry, rhyme was an anathema, a tool of the past bearing the insignia of conformity. Most of the songs I write now, though, revel in rhyme. More and more I’ve grown to understand and appreciate the utility of rhyme in songwriting and the radically paradoxical freedom it endows in its constraint. Sure, rhyme can be embarrassingly sophomoric as in “Love Me Do,” but more often, it becomes a vehicle to style and originality.

The best analysis of rhyme I’ve ever read is Adam Gopnik’s recent New Yorker essay “The Rules of Rhyme.” Reviewing Levin Becker’s book What’s Good: Notes on Rap and Language, Gopnik identifies two approaches to rhyme in poetry and music: True Rhymers and Tumble Rhymers.

True Rhymers revel in the highbrow, strict, conservative world of straight rhyme. “Do, you, true,” a la The Beatles’s “Love Me Do” being one example. Songs coming out of the Brill Building in the fifties, most of early Motown, standards written by Sammy Cahn, or most traditional show tunes from the likes of Stephen Sondheim would be other examples from the True Rhyme catalog.

Tumble Rhymers, conversely, are faithful to slant rhyme; they are far more invested in the sonic nuances of dialect and in the playful ways words can be paired together to represent the beautiful imperfections of speech. Emily Dickinson was a master of tumble or slant rhyme. But so are Kanye, Lou Reed, Kendrick Lamar, and Randy Newman. Personally, I find songwriting committed absolutely to true or straight rhyme mostly boring. It’s predictable. I am more excited and surprised by the witty innovation of rhymes that work only because of the way they’re delivered — the power of intonation mixed with timbre layered in mood. Tumble Rhymers are cool because they sculpt language, because they rhyme with moxie and pluck.

When I am writing a song with rhyme, sometimes the straight, true rhyme serves the song. But most of the time I am looking for a slant rhyme that moves the song into an interesting place; I’m always looking for a word that no one sees coming (not even me). As Gopnik pointedly notes in his essay, “rhyme is a self-imposed constraint, and you get to choose your handcuffs.” Sure, writing a song with rhyme can be restraining, but writing within established boundaries can lead to incredible breakthroughs. Especially when you’re willing to bend the rules.

Gopnik’s right when he proclaims that rhyming makes language matter. So, as you wade through the ocean of words trying to write a song, seek words that shock, surprise, illuminate, beguile, and charm. Rhyme words that no one has ever rhymed before (even though they probably have; you’ve just never heard the song). Trust: what matters more than the perfection of rhyme is the impression and emotional truthiness of the sound. So please, don’t let rhyme get in the way of the song itself, and never let rhyme commandeer the process either. And remember, it’s okay to tumble your way to the truth.

Surviving Line To Line